Invalid Exploration Licences caused by True Fella v Pantoro

There are a number of articles written about the True Fella Pty Ltd v Pantoro South Pty Ltd [2022] WAMW 19 (True Fella case), where the Warden applied a strict interpretation of s58 of the Mining Act 1978. The Warden followed the precedent of Forrest & Forrest Pty Ltd v Wilson [2017] HCA 30 (Forrest Case) and applied it to an exploration licence application and deemed the exploration licence application invalid.

Absent, is an analysis of the heart of the matter; the government’s culpability in writing legislation that is not fit for purpose, DMIRS failing to provide guidelines that are in line with the legislation, and the courts (including the High Court) applying a legalistic view of the legislation instead of a common-sense view.

In reply to industry complaints, Bill Johnson, Minister for Mines, stated that all exploration licences will be secure. The same words were articulated in 2017 about invalid mining leases being secure after the Forrest Case. Five years later, nothing has been done!

True Fella raises a number of issues for companies. To state the obvious, confirming the validity of exploration licences; considering the past incompetence, do we trust the Minister’s statement? Amongst the issues are how to validate exploration licence applications, or granted exploration licences, if they are invalid. What is required to make a valid exploration licence application? How do I secure an exploration licence that contains a resource? With an invalid licence am I conducting illegal mining? If tenure was sold, have I breached my warranties of good standing in the Sale Agreement, and am I now liable for compensation? Is an IPO possible with invalid tenure?

Summary of the Case

True Fella and Pantoro both objected to each other’s competing exploration licence applications and agreed the Warden decide True Fella’s first in time compliance. The case hinged on whether True Fella’s s58 statement was compliant.

“Under the Mining Act, an application for an exploration licence must be accompanied by a statement under s 58(1) (s 58 statement). A s 58 statement must state the proposed method of exploration in the application area, the details of the programme of work proposed to be carried out in the area, the estimated amount of money proposed to be spent on exploration and the technical and financial resources available to the applicant”[i]

True Fella had only provided the first-year programme of work and expenditure and stated that any further work depended on results of that expenditure, which is standard practice for the industry.

“Extraordinarily, the Warden found that s 58 of the Mining Act requires an applicant to:

- provide a programme of work for the full term (5 years) of the exploration licence;

- specifically identify the areas of the exploration licence which are to be subject to the exploration and the reasons for choosing those areas; and

- provide a proposed budget for the full term and for the full area of the exploration licence.”

The Warden also stated the s58 statement should:

- identify the minerals or the areas to be targeted in exploration; and

- may even need to identify a rationale for targeting certain minerals.

As part of the s58 statement was copied from True Fella’s Website, the Warden commented that the statement was deficient, claiming it contained only broad statements of True Fella’s technical capacity. Such broad statements were not sufficient for the Warden, nor considered connected to True Fella’s programme of work.

Ultimately, the Warden found the application invalid. In effect, the application did not exist because it did not comply with s 58(1) of the Mining Act.

It is standard practice in the industry to provide only the first year’s exploration programme and expenditure amount. Therefore, it can be assumed every exploration licence in the State could be invalid.

AMEC’s Response

AMEC responded swiftly to the True Fella case by sending a letter to Bill Johnson, Minister for Mines. Johnson replied with a motherhood statement that all exploration licences were safe. A very inadequate response as only a change in the legislation can validate current exploration licences.

The Government Legislation

To understand and analyse the current Mining Act, we need some historical context.

The Mining Act 1978 was written 44 years ago, in a different era. Seatbelts were just made compulsory, an enquiry into oil drilling on the Great Barrier reef was announced, and Germaine Greer published the Female Eunuch. Computer technology was in its infancy, the first computerized spreadsheet program was introduced, and the Apple computer was just released. Mobile phones didn’t exist.

In 1978 you could apply for an exploration lease, it would be granted 2 weeks later, and drilled the following week. If nothing was discovered, surrendered in the following week.

Native Title was introduced in 1996, getting tenure granted required negotiation with the Native Title Claimants, complicating the process. It now takes 2 years of struggle through a bureaucratic process to be granted tenure, and another 12 months to commence exploration, after the company approves the budget and DMIRS approves a POW.

Explorers used a loophole in the legislation and pegged mining leases, which would never be granted because of Native Title, over the whole of their exploration licences. This negated the need for 50% surrender in years 3 and 4, and guaranteed an endless lifespan for exploration licences.

In 2006, to counteract this problem, the government amended the Mining Act, so when applying for a mining lease a mineral resource was required. A mining lease application needed to be accompanied by a mining proposal, or a mineralisation report and a mining operations statement.

The High Court handed down the Forrest Case in 2017, stating legislation must be exactly abided by and non-compliance with the application process was ‘fatal to the validity’ of the mining lease. This decision invalidated a couple of hundred mining leases that are still invalid today.

This decision set the precedent for several other decisions including Forrest v O’Sullivan and the True Fella Case. Golden Pig Enterprises Pty Ltd v O’Sullivan [2021] WASC 396 (Golden Pig) ensured the Forrest Case applied to all exploration licences.

Section 58 of the Mining Act lasted 44 years without change or interpretation by the courts. One must ask how often it was relevant to the grant of an exploration licence, or was it a superfluous piece of legislation added by a government in a bygone era.

Comments on the Wardens Decision

Despite an exploration licence taking approximately seven years from the point of application to the end of the five-year term, the politicians and courts must believe geologists are clairvoyant to think they can:

- provide a programme of work for the full term (5 years) of the exploration licence;

- specifically identify the areas of the exploration licence which are to be subject to the exploration and the reasons for choosing those areas; and

- provide a proposed budget for the full term and for the full area of the exploration licence.

There are so many strategic decision points that set the course of exploration; what mineral is the markets darling during its term, governed by the commodity prices, capital raising, shareholder enthusiasm for funding.

During the exploration period, the latest scientific geological modelling or sampling techniques, the results of soil sampling or rock chip programme, the results of drilling programme, and resource calculation would all need to be considered.

MinEx Consulting stated in Market Failure in the Australian Mineral Exploration Industry: “Realistically, a well-considered and executed precious or base metals exploration program would have a gestation period of several years.”

Furthermore, numerous mega trends are impacting the mining industry, from ESG considerations, through to the use of advanced technologies such as Internet of Things (IoT) devices, AI, and digital twins, development in workplace safety, and Covid-19 pandemic whose spectre still looms on the horizon.

Providing, budgets and exploration programmes within such variability is impossible. It is like predicting monthly weather forecasts for the next 8 years.

Yet the Warden states:

- “to provide sufficient information to persuade the registrar, warden or Minister that the applicant is able to effectively explore the land”, Para 46

- “the Act requires a description not only of the applicant’s plan and planned expenditure in the first year, but for the life of the licence, and for the full area of the licence” Para 49

- “However, caution must be exercised not to overstate the type of material necessary to satisfy the requirements of s 58(1)(b). In determining that level of detail, reference must be made to the principles of the Act and the mining regime and the wording and context of the section” Para 55

For exploration companies to comply with s58 of the Mining Act, the Courts are asking them to write compositions of complete fiction, because the world is rapidly changing. The legislation, DMIRs and the Courts are then knowingly making decisions on these fictitious reports.

The government needs to rectify the problem in a multi-facetted manner, commencing with validating exploration licences stuck in limbo.

Government validating Exploration Licences

When validating exploration licences, the Government will probably run into the same problems as with validating mining leases caused by the Forrest Case; the Native Title Act will require amending.

The Mining Amendment (Procedures and Validation) Bill 2018 (WA) (Validation Bill) was introduced to validate all previously granted mining tenements, as a means of combatting the ramifications of the Forrest Case. The Validation Bill stalled partway through the legislative process, as the WA Government came to the view that amendments to the Native Title Act 1993 by Federal Parliament are needed first, to avoid complications associated with retrospective validations triggering the ‘future act’ regime under the Native Title Act.

The NTA was amended last year and lacked any reference to validating the WA mining leases. Now with Labour in power and the balance of power held by the Greens and Teal independents, it is even less likely to occur.

The State Government should do what should have been done in 1996 – negotiate a settlement with the NT parties. This could allow exploration companies to explore within WA without each company singularly negotiating with native title parties for the grant of each tenement; a process that creates an administrative nightmare, soaking up time and resources more productively spent elsewhere.

Protecting your assets

So, while the government procrastinates, what should you be doing to protect your assets, if you have not already done so. I qualify the following in stating that it is not legal advice and if you are in any doubt, seek a lawyer’s advice.

Check that your exploration licences, both granted and pending, contain the required information in s58 statements as stipulated by the Warden in the True Fella case.

If they don’t, apply for new exploration licences over existing exploration licence applications with new s58 statements that comply with the Warden’s view of the world. Updating existing s58 statements will not be accepted, as the licences just don’t exist.

If mineralised areas exist with an exploration licence, apply for mining leases over those mineralized areas.

Applying for new exploration licences over a granted exploration licence would require a risk analysis to compare the risk and reward of doing such; not forgetting the 3-month moratorium period to apply for the tenure as a related party. It will be interesting to see if DMIRS determines this applies considering the previous licence didn’t exist.

Amending the Mining Act

The True Fella Case drives another nail into the coffin of small exploration companies, excluding them from operating in WA.

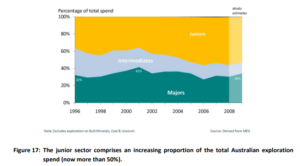

Small explorations companies are the life blood of exploration in WA, amassing most of the mineral discoveries in WA for the last 10 years. These discoveries are made by small, agile companies that can respond to market conditions and scientific advancements. Junior companies fund 50% of green field exploration, see graph below.

The assets of these companies need protecting. The Mining Act needs amending so that opportunists don’t exploit every loophole. So when mistakes are made by genuine explorers, they are not fatal to the exploration licence or mining lease, which exists in every other State in Australia.

There should be a complete change in the underlying philosophy of the Mining Act, which was constructed in another time, when computers didn’t exist and the assistance of the general public was required to assist in policing compliance with the Mining Act.

The WA Government and DMIRS need to take responsibility for making decisions in respect to tenure and not allow the wild west behaviour flourish, as shown in the Forrest Case and now in the True Fella Case. The advent of the computer since 1978 makes it possible for DMIRS to police compliance, here in the 21st century with the touch of a button and relative ease. There is no reason that an opportunist needs to issue an Applications for Forfeiture, Plaints or Objections, if compliance were legislated and governed by DMIRS.

In summary the True Fella Case is a disaster of epic proportions that the government needs to address quickly and strategically to redirect the underlying philosophy of the Mining Act and ensure security of mining tenure, and ultimately the industry.

To learn more about compliance in the mining industry, LandTrack Systems offers several Training Courses:

Understanding Tenement Expenditure

Navigating Exploration Agreements

[i] Forrest & Forrest strikes again – your exploration licences may be at risk Hopgood Gamin Partners, Paul Harley and Sarah O’Brien-Smith along with Solicitor, Ruth Kooy