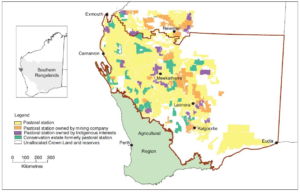

In 2016, there were 491 registered pastoral leases covering the better part of WA; 436 operating pastoral stations: 152 stations in the Northern Rangelands (92 in the Kimberley and 60 in the Pilbara); and 284 stations in the Southern Rangelands (shown in the image below). Lease ownership includes large corporations, private companies, family operations, Indigenous organisations, and, particularly in the Pilbara and Goldfields, mining companies.

The pastoral lease legislation contained in the, Land Administration Act 1997 (LAA), is a historical relic. It is the primary cause of the degradation of the WA rangelands as it lacks the versatility to allow other uses of the rangelands. The Pastoral Lands Board (3 out of 7 who are pastoralists) oversee the legislation, analogous to a wolf looking after the sheep.

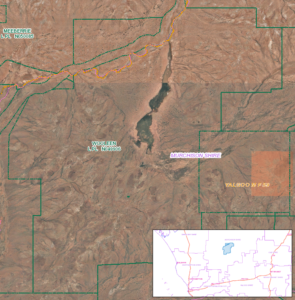

Over the last few weeks, I was reading the Wooleen Way by David Pollock, who has a non conforming pastoralist’s view of the world and how he is repairing the environmental damage on Wooleen Station. Pollock has a refreshing take; he recognised there was a problem and provided practical measures that he has implemented, and those that he will implement, to cure the problem. A welcome approach when compared to the State of Environment Report, produced every 5 years to gather dust in the archives, and nothing continues to happen.

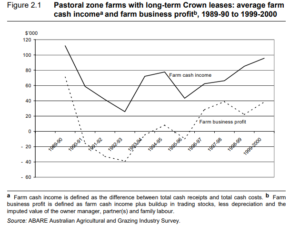

David Pollock hasn’t two-bob to rub together like most pastoralists (see the graphs below) and has turned to other means to supplement his income from his pastoral station, namely, tourism.

However, if the pastoral lands are managed pursuant to the LAA, it lacks flexibility for a pastoralist to alter the land use, and to raise revenue by any other means.

To allow for flexibility, the government is currently in the process of amending the legislation to introduce a new diversification lease, which is not concurrent tenure with the pastoral lease but replaces the pastoral lease. The LAA allows a pastoral lease to be turned into freehold land, but when Pollock attempted this, he ran into a bureaucratic roadblock, with the government blaming the problem that Native Title holder’s consent and compensation is required.

The fundamental cause of the rangelands environmental damage since the 1870’s is overgrazing by the combination of introduced and native animals: rabbits (mainly in the Nullarbor), sheep (whose numbers peaked in the 1930s), goats (a relative recent introduction), camels, donkeys, cattle, and kangaroos which increased with the increased water supply by windmills and related infrastructure.

Report Cards on WA’s Rangeland

The following is quoted from Report card on sustainable natural resource use in the rangelands of Western Australia dated 18 October 2021.

“In the southern rangelands, at the aggregate LCD [Land Conservation District] scale, vegetation condition was 36% good, 39% fair and 25% poor at the last assessment… the density of all shrubs and trees and desirable shrubs and trees has been variable since monitoring began in 1994, although density had predominantly decreased.

In the southern rangelands, vegetation cover decreased in three vegetation functional groups in the Gascoyne–Wooramel LCD, two functional groups in the Meekatharra LCD, and one functional group in each of the Lyndon and Cue LCDs… Some degree of soil erosion occurs throughout the entire rangelands, most notably in the Gascoyne and Murchison, and to a lesser extent in the Kimberley, Pilbara and Goldfields.

The Upper Gascoyne LCD has the highest level of recorded erosion, with 6% of the LCD with moderate to severe erosion… Soil organic carbon (SOC) levels in the WA rangelands are low by global standards, even in higher rainfall areas”

A survey of the Murchison River catchment between 1985-1988 produced a report that declared 42% of land to be in poor to very poor condition. Rangeland inventory and condition survey of the Murchison River catchment and surrounds, Western Australia was originally published in 1994, and is still referred to by the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development today.

To put this into perspective, this is the area of NSW in poor condition or eroded, and it needs active rehabilitation to restore the natural environment.

Don Burnside’s 1995 book said that 25% of the Rangelands were in poor condition (p14 Reading the rangeland: a guide to the arid shrublands of Western Australia 1995, Don Burnside etc). Recovery is slow due to the slow growth rate of the shrubs (some of the blue bushes are estimated to be 300 years old), the intermittent rainfall, hot temperatures, and the nutrient deficient soil. Burnside states that the soil has 50% of the nutrients of normal soils because of the age of the continent.

“perennial shrubs have a high regeneration rate after defoliation which may result from grazing, fire or drought. (In fact defoliation may be a survival mechanisms for some shrubs in prolonged dry periods. If they have no leaves, they need not continue photosynthesis!) But if shrubs face a second defoliation soon after recovery from the first (perhaps due to heavy grazing), they often fail to survive”

The loss of the perennial grass and shrubs leaves only annual vegetation that is short lived after rain. All the everlasting daisies look great, but once annuals die off and the perennial shrubs are removed, there is no further vegetation to halt the wind and water erosion. Each perennial shrub creates its own micro-environment, capturing leaf litter and building up soil around it. When it does rain, the run-off is funnelled to the roots of the shrub.

The areas of poor vegetation are easily eroded and usually along the fragile alluvial country, due to its proximity to water.

“If soil is lost from rangeland through erosion, it is effectively lost forever as natural weathering of rocks and new soil formation are extremely slow” p15 Reading the Rangeland.

Therefore, Rangelands that are in a poor state require active participation for their regeneration. The problem is the pastoralists lack funds for living, let alone regeneration.

Regeneration

Pollock was initially of the view that removing the grazing animals would allow the vegetation to recover. A variety of other methods were used, removing the sheep and cattle, trapping goats, shooting the kangaroos and camels, and cessation of poisoning the dingos (an apex predator) that breed and preyed on kangaroos and goats while keeping the foxes and cats at bay. The native animals in the rangelands have been decimated by wild cats and foxes.

Measures were taken to reduce erosion, barriers set up to slow the water, allowing it to soak into the surrounding countryside when it rains.

Unfortunately, Pollock’s removal of the grazing animals and other actions only assisted those parts of the rangelands that were in good to fair condition.

At the end of the book, he outlined several other proposals for rehabilitating Wooleen:

- Retaining the rain on the pastoral lease by a number of methods, vegetation and artificial barriers, restructure roads and fences and to prevent runoff.

- Re-establish perennial bushes and grasses.

- Putting in more water points to increase the rotation period of the stock around the lease to prevent over grazing, and to spread manure/fertilizer.

- Building a large dam, with gravity feed to water troughs, located on hill tops so when it rains the manure accumulated there washes down the hill to the fertilizer the plants.

- Establishing plant nurseries at the watering points, fully fenced areas to prevent grazing and allow seed production and dissemination.

- Currently, Pollock is buying and selling cattle depending on the season, a highly inefficient way to run a pastoral station. Establishing a permanent herd to rotate around the lease, enables the stock become accustomed to the shrubs, grasses, and water points.

- Stress free cattle movement, rewarding the cattle for moving with hay, molasses and cattle licks.

- Additional fencing to extending rotational periods.

- Virtual fencing, cattle wearing solar powered collars for directing by noise and electric shock.

- Reducing erosion by filling in eroded gullies, or creating dams which should reinstate natural soil levels.

- Re-establishing native fauna, which burrows into the ground. However, this would entail a dramatic decrease in cat population.

This list is important because it demonstrates that each pastoral lease has a bespoke method of rehabilitation. What works on one pastoral lease does not mean it will work on another and visa-versa.

The DPIs Attempts

The Department of Primary Industry and Regional Development (DPI) did not renew 25 pastoral leases in 2015 as it planned to convert the land to A Class Reserves. This failed to occur because of Native Title issues and the land reverted to Vacant Crown Land (VCL). They did remove all the water points to prevent the animals access to water and breeding and ultimately grazing.

The DPI has no answer for rehabilitation of the land, other than destocking and fire. They recommended the pastoralist incorporate sustainable rangeland management into their operations, which means:

- “monitoring rangeland vegetation condition

- balancing the short-term nutritional needs of livestock with sustaining the pasture base in the long term

- using information and technologies”.

Which is bureaucratic speak for destocking when necessary.

Mining Rehabilitation of Pastoral Stations

Pollock suggested the Government should be funding the pastoralist to rehabilitate their leases, but the DPI obviously lacks the imagination to undertake any sort of rehabilitation of the rangeland despite having the responsibility for its management.

Pollock made several observations and suggestions that mining companies undertake rehabilitation of the pastoral stations, which I thought particularly interesting; see chapter 18 of Wooleen Way.

To summarise it states:

In WA the $105M (2006 figures) spent on rehabilitation of mining waste dumps and tailings dams is of limited success, these areas compared to the rangelands of WA are very small. This money could be better spent.

If there is a choice between spending millions of dollars to grow a handful of hardy (therefore common) plants on a few hundred hectares of mining waste so that they appease the eye of the passing tourist, or the option of restoring the ecological balance and landscape function over 2 million hectares of adjacent rangelands, surely we would opt for the latter?

This would negate the problem of companies going into administration and not doing any rehabilitation, for which the Mining Rehabilitation Fund was established for.

The scarifying of drill sites and tracks for rehabilitation, required by DMIRS, is inefficient because it only encourages a few annuals to grow. Establishment of perennial shrubs is needed for proper rehabilitation.

The miners have the money and expertise, which the pastoralists lack, for this type of rehabilitation.

The Way Forward

Pollock’s actions are not accepted by the Pastoral Lands Board or by his neighbours. No one can afford to destock; however, it is essential for the continued environmental restoration of the Rangelands. At a guess, his suggestions may not be accepted by EPA or DMIRs either. I am captivated by how practical the suggestion is to rehabilitate the rangelands, and believe there is nothing to prevent mining companies going the extra mile, joining with the pastoralists and native title parties to rehabilitate the rangelands to its original state at settlement. This is a very practical way to garner ESG credits or ACCUs by rehabilitating the highly degraded rangelands, but requires the legislation to change to cater for pastoralists and mining industry’s requirements.