Australia’s mining sector has long been regarded as a cornerstone of the national economy, driving export revenue, regional development, and technological innovation. Gold, in particular, has held a special place in this story, from the transformative gold rushes of the nineteenth century through to today’s world-class mining operations.

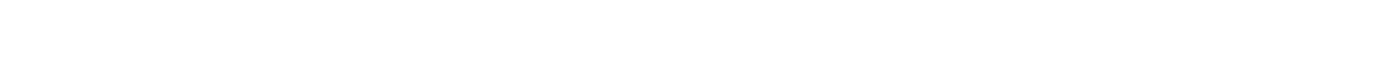

In 2025, gold continues to dominate global attention as both a safe-haven asset and a driver of exploration activity. Yet despite record or near-record gold prices, the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ June 2025 figures reveal an uncomfortable paradox: while gold exploration expenditure surged by 36 per cent in the June quarter to A$400.1 million, greenfields exploration fell by 17 per cent year-on-year, slipping from A$305.6 million to A$253.2 million (ABS 2025).

This outcome is surprising, counterintuitive, and concerning, particularly as greenfields activity underpins the long-term discovery pipeline needed to ensure the future prosperity of the industry and, by extension, the national economy.

AMEC Chief Executive Warren Pearce described the decline as “the most concerning for our industry” because it reflects not just immediate economic decisions but deep-seated issues of regulation, governance, and investor sentiment (AMEC 2025).

To understand this paradox, one must first consider the behaviour of investors in resource markets. Mining exploration is inherently high risk: most grassroots drilling campaigns fail to deliver a commercial discovery, and those that do often require a decade or more of additional investment before production begins.

When macroeconomic uncertainty is high—characterised by inflation, high interest rates, and volatile equity markets—capital tends to flee riskier investments in search of stability. In this environment, brownfields programs, which expand or extend existing deposits, are far more attractive than greenfields undertakings.

Brownfields projects usually benefit from established infrastructure, known geology, and shorter paths to production. They offer the possibility of relatively rapid returns, which is particularly appealing when investors are cagey about long-term commitments.

By contrast, greenfields exploration requires patience and deep pockets. The gap between investor appetite and exploration needs has therefore widened, producing a cycle where grassroots projects are repeatedly deferred in favour of safer brownfields campaigns.

The regulatory environment exacerbates this cautiousness. Exploration companies consistently highlight the challenges of navigating Australia’s complex permitting system. Approvals are often fragmented across federal and state jurisdictions, with requirements for environmental assessments, cultural heritage consultations, and land-use negotiations.

While these obligations are essential to protect natural and cultural values, the processes are frequently protracted and inconsistent, producing uncertainty that deters capital. A permit that may take six months in one jurisdiction can take two years in another.

This inconsistency makes investment planning more difficult and encourages companies to concentrate on ground where approvals are already in place. Land access is another challenge: agricultural, conservation, and renewable energy projects all compete for the same terrain, adding friction to the permitting process.

At the same time, cost inflation has been relentless. Exploration drilling is highly sensitive to cost pressures in labour, fuel, consumables, and equipment. The post-pandemic environment has seen chronic shortages of skilled geologists and drill crews, higher diesel and transport costs, and supply chain bottlenecks that have increased the cost of consumables such as drill rods and explosives.

For smaller companies, which rely on raising capital from equity markets, these rising costs can be prohibitive. Faced with limited funds, juniors often redirect spending toward projects that can quickly deliver JORC-compliant resources, scoping studies, or near-term cashflow opportunities, usually in brownfields settings. This contributes further to the decline in greenfields campaigns.

Perhaps most corrosive to investor confidence, however, are persistent governance concerns. The label of “lifestyle company” has haunted the junior exploration sector for decades, describing those that raise money on the market but spend little of it in the ground, instead funding director salaries, promotional campaigns, and corporate overheads.

Although not representative of the entire cohort, the existence of such companies erodes investor trust. The fear of funding another lifestyle company often results in caution even toward credible juniors. This problem is not merely anecdotal:

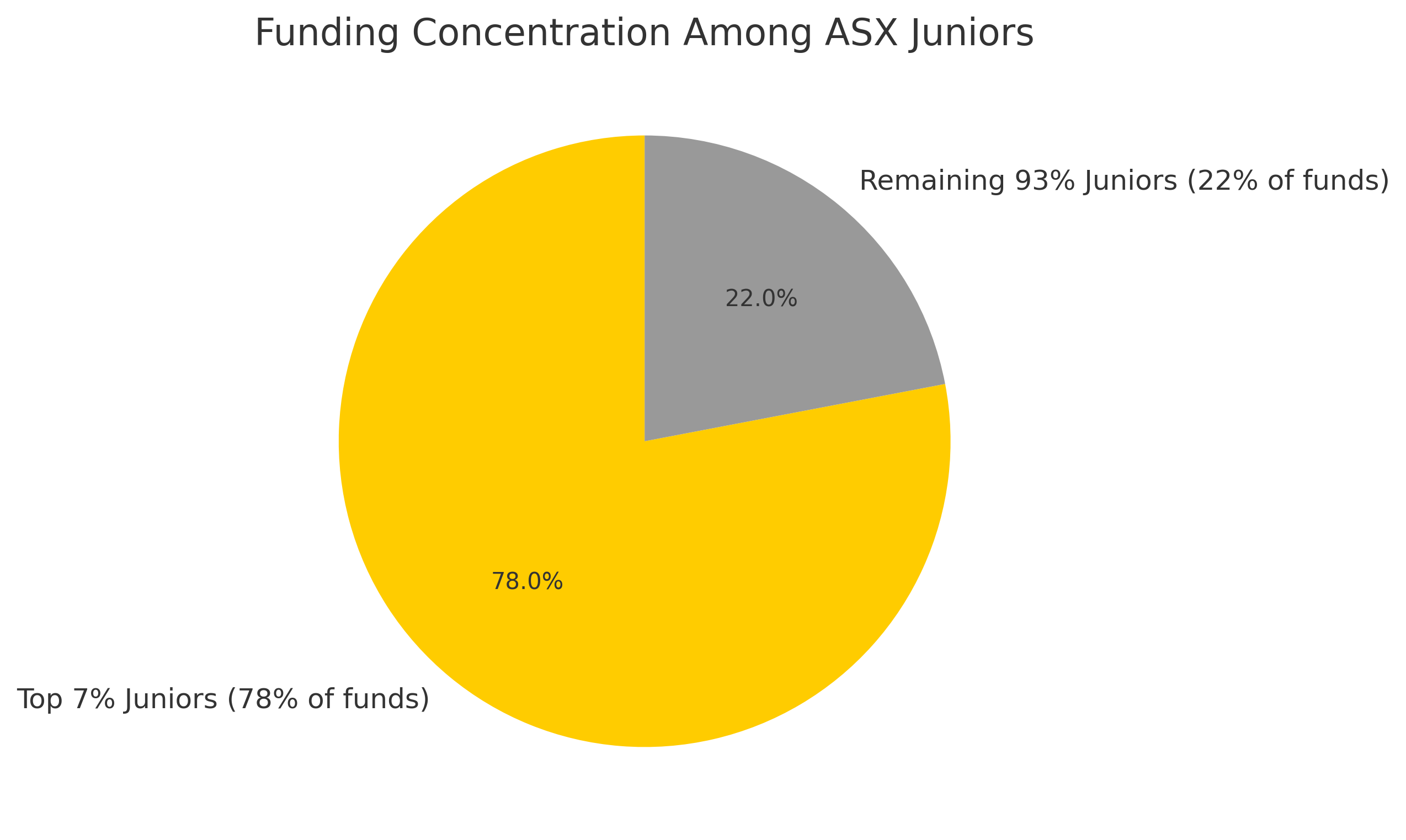

BDO’s Explorer Quarterly Cash Update reveals that just 7 per cent of ASX-listed junior explorers captured 78 per cent of new capital raised, leaving the remaining 93 per cent to fight over just 22 per cent (Stockhead 2025). With approximately 600 resource-focused juniors listed on the ASX (MinEx Consulting 2014), this suggests that well over 500 are significantly undercapitalised.

Such concentration of capital not only hobbles the ability of genuine explorers to finance drilling campaigns but also pushes the majors toward acquisition rather than discovery.

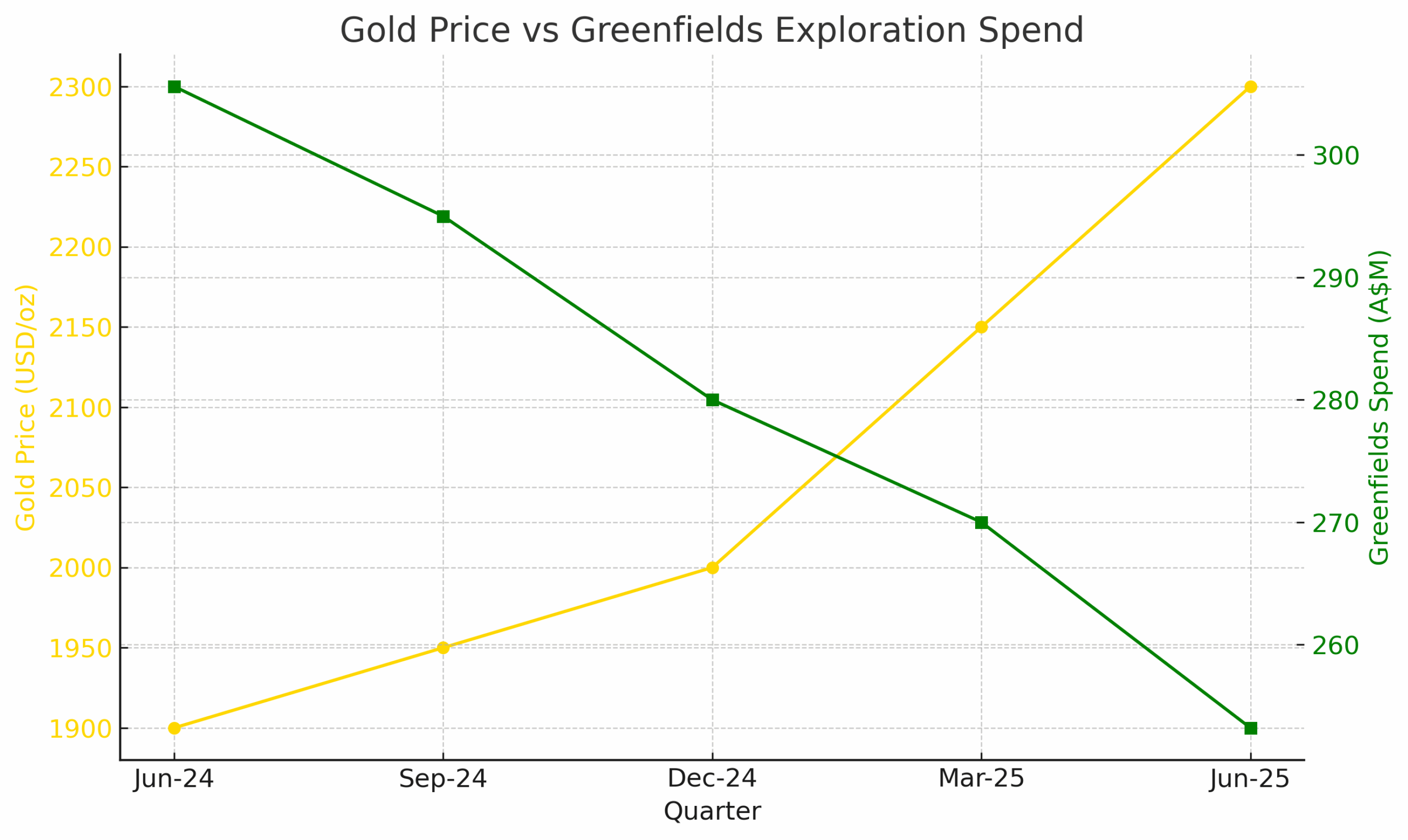

Indeed, the behaviour of major gold companies highlights another structural problem. In recent years, large players have increasingly chosen to acquire juniors with proven deposits rather than fund grassroots exploration themselves. Acquisitions offer immediate ounces to bolster reserves and reassure shareholders, while exploration carries long timelines, high risks, and uncertain payoffs.

From the perspective of a major, the choice is clear: buy rather than drill. While this strategy makes sense in the short term, it carries long-term risks. If juniors are underfunded and fewer discoveries are made, the pool of acquisition targets will diminish, leaving majors without sufficient options to replenish their pipelines. The result is a slow erosion of the discovery ecosystem.

Compounding all these issues is global competition for exploration capital. Australia is no longer the only attractive destination. African jurisdictions such as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Tanzania are aggressively marketing themselves to international explorers with incentives, streamlined approvals, and proactive government support.

For investors, the trade-off is clear: while political risk may be higher in parts of Africa, the regulatory environment is faster, cheaper, and less complex. Exploration costs per metre drilled can be significantly lower, and projects can move from exploration to development in shorter timeframes.

Latin American countries, too, are competing for attention, and Canada continues to attract substantial exploration dollars, supported by programs such as flow-through shares that channel private capital directly into exploration expenditure. Australia, by comparison, risks being perceived as expensive, slow, and mired in red tape.

History provides useful perspective. Australia’s gold sector has long been cyclical, with booms in the 1850s, 1890s, and 1980s each reshaping the national economy. Each time, new greenfields discoveries played a pivotal role: Ballarat and Bendigo in the nineteenth century, the Kalgoorlie Super Pit in the twentieth.

These discoveries not only fuelled immediate prosperity but underpinned decades of production. Without equivalent greenfields investment today, the nation risks relying on existing mines until they are exhausted, without the next wave of discoveries to replace them. This would mark a profound break in a historical pattern that has defined Australian mining success.

Policy responses are therefore critical. One of the most promising initiatives is the Junior Minerals Exploration Incentive (JMEI), which converts tax losses into exploration credits for investors.

Introduced in 2017–18, the JMEI has delivered A$190 million in credits, generating A$404 million in exploration spend, A$1.2 billion in junior capital raising, A$391 million in government revenue, A$769 million in GDP impact, and an estimated A$5.9 billion in mineral production (AMEC 2024).

However, the program is consistently oversubscribed and only reached 34 juniors in FY22–23 (MarketIndex 2022). Expanding JMEI’s coverage could dramatically increase its effectiveness, spreading benefits more widely and ensuring that more companies can translate capital into drilling.

International examples, such as Canada’s flow-through share scheme, demonstrate that targeted incentives can transform capital raising for juniors.

Governance reforms are equally important. Requiring disclosure of the proportion of capital spent “in the ground” versus administration would provide investors with greater transparency. Stricter ASX reporting requirements and enhanced oversight of director remuneration could also curb lifestyle behaviours. Industry associations such as AMEC could spearhead voluntary codes of conduct, promoting accountability and raising the baseline standard across the sector. These changes would not eliminate all risk, but they would help rebuild the trust essential for unlocking investor appetite.

Public-private geoscience partnerships represent another avenue. Pre-competitive geological surveys funded by government can reduce exploration risk, lower costs for juniors, and attract capital by highlighting prospective regions.

Australia has a strong tradition of such programs, and expanding them could give juniors the confidence to pursue greenfields exploration. Similarly, investor education programs—helping retail and institutional backers distinguish between credible and questionable explorers—could support better capital allocation.

If these reforms are implemented, Australia could turn the current paradox into opportunity. High gold prices provide a rare window: if capital can be redirected into greenfields exploration, the country could secure the discoveries needed for the next generation of mines.

Without such change, however, the discovery pipeline will erode, leaving the sector dependent on acquisitions and foreign discoveries. This would weaken Australia’s resource sovereignty and diminish its ability to sustain mining as a pillar of national prosperity.

In conclusion, the decline of greenfields exploration in Australia at a time of surging gold prices reflects a convergence of investor caution, regulatory barriers, cost inflation, governance failures, major company strategies, and global competition.

It is not a temporary blip but a structural issue that threatens the long-term vitality of the nation’s resource sector. History shows that Australia’s prosperity has always been built on new discoveries; without them, production will eventually decline. Policy reform, governance improvements, targeted incentives, and renewed commitment to greenfields exploration are therefore essential. G

old’s current strength provides an opportunity that must not be wasted. If Australia can mobilise to rebuild investor confidence, streamline approvals, and strengthen governance, it can secure not only its mining future but its broader economic resilience. If it fails, the paradox of high prices and low discovery may become a permanent feature—one with profound consequences for the national economy.

Discover more about the gold mining industry by attending LandTracks Training Courses. Dates for the remainder of 2025 are:

- Practical Tenement Management (PTM): 23–24 October 2025

- Environmental Essentials: 30–31 October 2025

- Advanced Tenement Management: 13–14 November 2025

- Understanding Tenement Expenditure: 4–5 December 2025

References

ABS (2025) Mineral and Petroleum Exploration, Australia, June quarter 2025. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

AMEC (2024) Junior Minerals Exploration Incentive (JMEI): Economic Contribution. Perth: Association of Mining and Exploration Companies.

AMEC (2025) AMEC media release, June 2025 quarterly results.

BDO (2025) Explorer Quarterly Cash Update, March 2025 Quarter. BDO Australia.

MarketIndex (2022) Junior Minerals Exploration Incentive (JMEI), MarketIndex.

MinEx Consulting (2014) Long-term forecast of Australia’s mineral exploration.

Stockhead (2025) “M&A a must in 2025 as explorers see cash dry up,” Stockhead, citing BDO Quarterly Update.

World Gold Council (2025) Gold Demand Trends.

Fraser Institute (2024) Annual Survey of Mining Companies.