Special Prospecting Licences (SPLs) were added to WA’s Mining Act 1978, a window of opportunity for genuine prospectors chasing small, shallow patches of gold overlooked by the big players. The intent was clear: to preserve the old spirit of individual discovery in a mining landscape increasingly dominated by corporations.

But decades on, that spirit has been eroded. What began as a tool for battlers with metal detectors has become a loophole ripe for exploitation. SPLs, once the preserve of individual prospectors, are now being traded, warehoused and leveraged by the very interests they were meant to exclude.

Instead of levelling the playing field, the system is being gamed — turning a licence for opportunity into a vehicle for control.

The irony is striking: a mechanism designed to keep prospecting alive may now be undermining it, locking up ground and distorting access to resources in ways the lawmakers of 1978 could never have imagined.

Under section 56A, a SPLs can be applied for within a Prospecting Licence, provided that licence has been granted for at least twelve months. Section 70 applies the same principle to Exploration Licences, with the same twelve-month threshold. Section 85B covers applications within Mining Leases, but in that case the written consent of the mining leaseholder is required and there is no waiting period.

In all cases the SPL is restricted to a maximum area of ten hectares and may only be held by individuals. No more than ten SPLs can be held by any person at one time. The licence is for gold only, and although it is technically granted to an unlimited depth, the Mining Act places practical limits. The default depth is fifty metres, unless a shallower limit is negotiated with the primary holder, or the Minister agrees to allow a deeper limit.²

Procedurally, the application process mirrors that of a Prospecting Licence. Applicants must serve a Form 21 notice on the primary holder, who then has the right to object. If an objection is lodged, the Warden must obtain a report from the Executive Director of the Geological Survey, based solely on the primary holder’s statutory reports. The Warden then decides whether the SPL can be granted without causing undue detriment to the primary holder’s activities.³

In the case of Mining Leases, the requirement for written consent means the objection procedure does not apply. The maximum term is four years, granted in multiples of three months or more, and the licence cannot be renewed. If granted for the full four years, an SPL can be converted into a Mining Lease for gold, provided the holder has met expenditure and reporting obligations. This creates a pathway from small-scale prospecting to more significant operations.⁴

On paper the framework appears balanced. It preserves the rights of the primary tenement holder while offering space for small prospectors to operate.

Yet practice has diverged from intention. Recent complaints to the Minister of DMPE have highlighted a pattern of SPLs being pegged just before primary tenements expire. By doing this, individuals can effectively bypass the midnight pegging system, which was designed to give everyone an equal chance at newly available ground.

Instead of SPLs functioning as a grassroots tool, they become a tactical instrument for speculation. Companies can find themselves forced into Warden’s Court disputes or into buying out SPL holders simply to proceed with legitimate exploration or development. The fairness of the system is compromised, investor confidence can be weakened, and grassroots exploration is distorted.

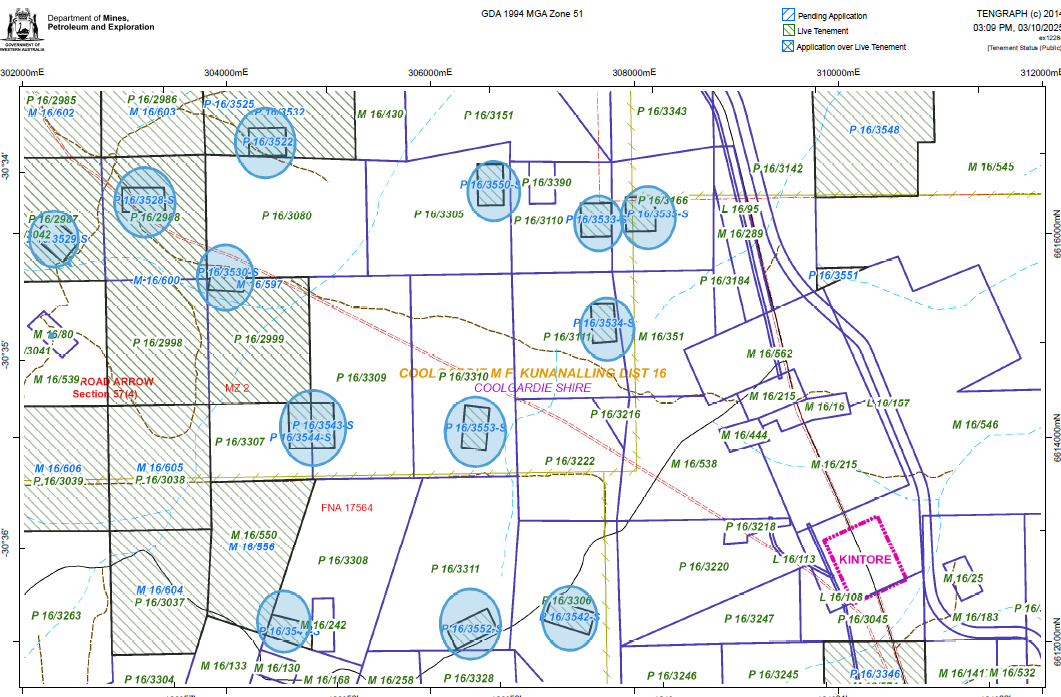

See the attached map from the Kalgoorlie region illustrates how this works in practice. SPLs have been lodged in bulk over tenements nearing expiry, including areas with little prospecting potential. In some cases SPLs have been pegged over pit waste dumps and ground already defined by drilling. The pattern suggests that the motivation is not to conduct genuine shallow prospecting, but to gain strategic control over ground ahead of others.

Industry and government perspectives on SPLs add another layer. Anecdotally, within government, SPLs are often regarded as anachronistic, a quirky holdover from an earlier era that has been tolerated rather than modernised. Prospectors argue that SPLs contribute to discovery, but their contribution is often overstated, while gold miners tend to tolerate them and self-regulate relationships with prospectors.

Policymakers, meanwhile, are cautious. Reforming or removing SPLs risks provoking backlash from vocal prospectors, and the political calculation is whether the gain of cleaning up the system is worth the pain of the confrontation. Even the Prospectors Association has recently asked whether government is “coming after SPLs,” a sign that prospectors themselves sense pressure is building for change.

There are clear points in the legislation that invite reform. The twelve-month requirement for eligibility does not prevent last-minute pegging near expiry. The conversion pathway to Mining Leases gives SPLs a speculative value far beyond their intended purpose. The rule that only individuals may hold SPLs has not stopped coordination among associates. And the objection procedure, while designed to protect primary holders, is reactive and costly to pursue. Case law has also signalled the limits of SPL leverage.

In Pilkington v Kurnalpi Gold [2024] WAMW 27, the Warden held that an earlier Mining Lease application by an exploration licence holder took priority over a later conversion attempt by an SPL holder. That decision affirms the principle of “first in time” and curtails some of the strategic value of SPL conversions, but it does not resolve the broader fairness issues.⁵

Reform options have been suggested. One would be to prohibit SPLs being pegged within twelve months of the expiry of a primary tenement, closing the pre-expiry loophole. Another would be to tighten the rules for conversion to Mining Leases, requiring demonstrable shallow gold and actual prospecting activity before a conversion can be considered.

Transparency requirements could be introduced, compelling applicants to declare intended work programs and demonstrate capability. Proximity restrictions could prevent clustering of SPLs near expiring ground unless justified. Procedural improvements, such as clearer notice and service obligations under Form 21, would also strengthen fairness.

The future of Special Prospecting Licences comes down to a choice. They can be reformed, tightened and restored to their original purpose of enabling genuine small-scale prospectors to responsibly work overlooked ground. Or they can be allowed to persist as an outdated relic, tolerated for the sake of tradition but increasingly at odds with the modern mining system. Either way, the conversation about SPLs exposes a fundamental truth.

Tenure systems survive on fairness. When fairness is eroded by loopholes and opportunism, confidence falters. For Western Australia’s mineral industry, where trust in the system is as valuable as the gold itself, that is a risk too significant to ignore.

Discover more about the gold mining industry by attending LandTracks Training Courses. Dates for the remainder of 2025 are:

- Practical Tenement Management (PTM): 23–24 October 2025

- Environmental Essentials: 30–31 October 2025

- Advanced Tenement Management: 13–14 November 2025

- Understanding Tenement Expenditure: 4–5 December 2025